Artículo publicado en Third Palenque Round Table (parte 2), páginas 151 a 162, editado por Merle Greene Robertson, University of Texas Press, Austin and London, ISBN 0-292-78037-0, Austin, Texas, USA, y que es una recopilación de la Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque, evento realizado del 11 al 18 de junio de 1978.

We all know that architecture is a very important and instinctive feature of the civilization of all peoples. This is because of the leading role of architecture, which is not merely formal but also functional and ideological. The significance of architecture goes far beyond the simple construction and utilization of buildings, inasmuch as it has been, throughout history, a key element both in religion and in the structuring of states. It becomes a symbol, an activity implying massive participation and some kind of social organization as well as availability of the necessary materials and techniques.

We also know of the many ideological implications of architecture and of its function as a social communicator. At the same time, it is the longlasting representation of dominating patterns.

If we look back upon the history of civilizations, we realize that most examples selected by social historiaras to illustrate each culture are from its architecture, inasmuch as they represent a way of life, a whole body of ideas, collective and individual hopes, and of course the abilities and aims of humankind and its true achievements.

Thus we find, within pre-Hispanic America in general and Mesoamerica in particular, architectural elements that represent something far beyond simply what they resemble. We want to analyze now a very particular case: that of templar-religious buildings having façades in the shape of large zoomorphic entrance passages.

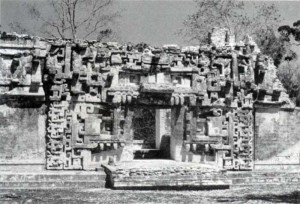

The first element to be taken into consideration is the wide area in which this phenomenon appears; it is found in sites as different as Tikal, Copán, the Río Bec region (fig. 1), Malinalco, Tenochtitlán, and many others. In Ecuador, too, it is found in miniature ceramic examples from the island of La Tolita.

Fig.1 Building II, Chicanná. An excellent example of a Maya temple in which the mouth of the monster is the doorway. Photograph by Paul Gendrop.

This means that we are presented with something quite unusual: the existence of a single element spread over many different regions, cultures, and epochs. We might think, perhaps, of an «invariant», as defined by Chueca Goitia (1971).

The idea of accepting this concept and not one of a «constant» is based upon our feeling that this pattern changed permanently through various times and cultures, adapting itself to different circumstances. We should keep in mirad that all symbolic values may be manifested in many similar ways, though they will not be the whole of a communicative process.

Fortunately we can now rely on a magnificent tool to work with in connection with meanings and communication media: semiotics, though it has been little applied to iconography. But semiology, even though it is a structuralistic science, clearly shows us the mechanisms through which we can establish the differences between significances and communication, so as to find the signs and their codes, enabling us to improve our understanding of communication processes with the aim of achieving, one day, a correct decodification of certain pre-Hispanic expressions (Eco 1978).

We should like to start with a discussion of the American Formative Period in general, in which we might find the origins of such a typical characteristic.

Both of the most studied Formative American cultures, Chavín and Olmec, present some features which we have already considered in connection with this general idea: the jaguar-cave link and the human figure emerging therefrom with a newly born child.

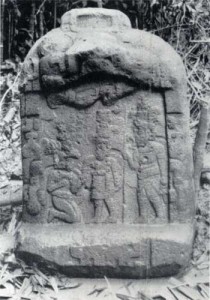

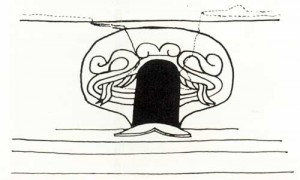

It should be remembered that this motif is very widespread among the Olmec; we have it represented in Altars 2, 3, 4 (fig. 2), 5, 6, and 7 at La Venta, in Stela 1 of the same site, in Stela D of Tres Zapotes (fig. 3), in which there are three figures inside the open mouth of a jaguar, in Monument 5 at Laguna de los Cerros, and in Monument 14 at San Lorenzo.

Fig.3 Stela D, Tres Zapotes. A ritual scene involving three figures in the mouth of a jaguar. After Kubler 1975: pl 41.

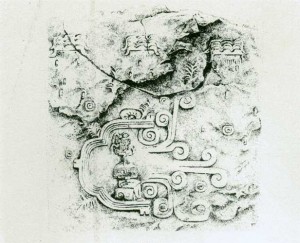

The motif is also repeated in the mural paintings of the Oxtotitlán cave and in the reliefs at Chalcatzingo (fig. 4). In Grove’s (1973) view, this could be identified with the origins in the underworld, the cave representing the latter, and the birth of the jaguar child, the result of some union in that dark and deep interior world.

Fig.4 Chalcatzingo Petroglyph 1. The rain deity is seated in the jaws of a jaguar which represents a cave from which stylized volutes (clouds) issue. After Kubler 1975: pl. 42.

Joralemon (1971) is of the same opinion; he associates the cavern with the mouth of the jaguar, and he considers it the determining feature of God L, the chief god in Olmec mythology. We can observe him in the big frontal mouth of Chalcatzingo’s Relief IX (fig. 5), and we believe this mouth could have been used as a small doorway. We think this can be linked to such habits as dressing in the skin of a jaguar, which is of great importance among the Olmec, the Maya, and many other cultures, and which we can observe in thousands of ceramic figures.

Fig.5 Relief IX, Chalcatzingo. The large mouth of a jaguar which forms the door is thought to be associated with the underworld. After Grieger 1970.

There is a very interesting vase from the Olmec culture showing graphically decorated huts. The huts, probably belonging to farmers, are surrounded by lines that could be interpreted as a large stylized face that seems to frame them; this, in fact, can also be observed in Uxmal, in spite of some obvious differences (Drucker, Heizer, and Squier 1959: fig. 69).

As to Chavín, although all these elements do not show up so clearly, the link between jaguars, caves (Chavín de Huántar tunnels), open entrance passages, and snakes is also evident (Badner 1972).

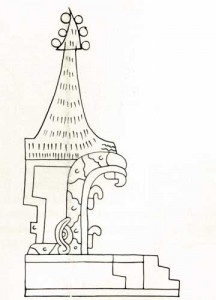

Later this will appear again in the Chiapaneca region of Izapa. Based on many iconographic researches that have been carried out, we are able to identify a variety of scenes, all taking place within the stylized open jaws of the jaguar monster of the earth, represented on stelae and monuments.

From what we know, the Izapa style is intermediate between Olmec and Maya art, and elements common to both conventions are found in these reliefs. Quirarte (1973), who thoroughly analyzed these motifs, is of the same opinion.

As to the art of Izapa, we can rely on a study carried out by Quirarte, in which he worked on representations of the so-called polymorphs. These are varied combinations of animals usually corresponding to heaven and earth expressions. Actually the differences between heaven and earth animals in Izapa art are not clearly defined, though there can be no doubt about their existence. Quirarte believes that they have to do with the open jaws of a feline-saurian-snake element, relating them also to the later façades of the Chenes region.

It is interesting to note that these scenes show an initial and clear division of the composition into an upper and a lower section and that later they all became one single and full rectangle comprising a whole design. This could possibly be the intermediate step between the Olmec idea of a single animal (which at this point became divided into two) and the Maya system in which we find a clear definition of the monster of the earth and the heavenly snake. However, it is remarkable to see that in such sites as Palenque, for instante, that difference is not very noticeable; on the contrary, the scene is often developed within a continuous framework, most often altogether abstract. The stelae of Izapa are chronologically dated between about 500 B.C. and the year 0.

Without going further into the Formative Period, we can say at this point that we do have a pan-American «invariant», something like a prime myth in which jaguars, caves, birth, the underworld, and various terrestrial monsters, particularly the snake, play a leading role. The association mouth-jaguar-cave-earth might be its principal expression.

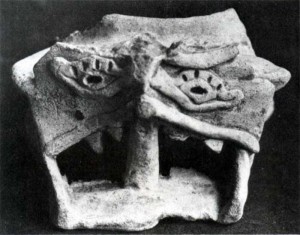

In South America, particularly in Ecuador, there are found a number of ceramic figures representing buildings (figs. 6-9). Most of them come from La Tolita, Glose to the present border with Colombia, and show façades with zoomorphic features, which leads us to interpret them as religious buildings. Unfortunately we are unable to find archaeological remains of temples with their façades still standing, and even less with their decorations intact (Schávelzon 1977), and that is why these architectural models from this region are so valuable.

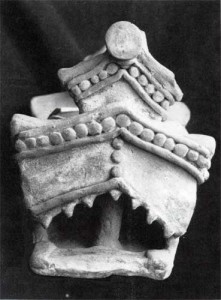

Fig.6 This ceramic model of a temple resembles an animal whose open jaws form th doorway. La Tolita, Ecuador. Collection of the Museo Arqueológico del Banco Central.

Fig.7 Pre-Hispanic model of a temple. Teeth line the upper portion of the doorway (mouth of the animal). Ecuador. Collection of the Museo Arqueológico del Banco Central.

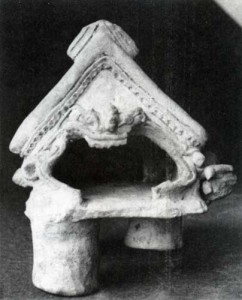

Fig.8 A perfect symbiosis between animal and archictecture. The animal´s leg can be seen on the side view as well as the mouth – doorway in front. Photographs courtesy of Dirección Nacional de Patrimonio Artístico.

Fig.8b A perfect symbiosis between animal and archictecture. The animal´s leg can be seen on the side view as well as the mouth – doorway in front. Photographs courtesy of Dirección Nacional de Patrimonio Artístico.

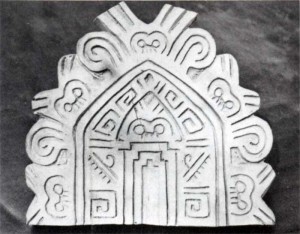

Fig.9 Seal of the Manteño of Ecuador, which represents the door of a building with zoomorphic decoration. Collection of C. Di Capua, Quito.

The models show varied degrees of detail in their design; we can see eyes, noses, and jaws with teeth or simply some overhanging teeth in the doors’ lintels. In other cases, the roof of the building is a huge mask. We have found a large seal showing a whole building decorated with these masks.

The aboye archaeological pieces are dated between approximately 500 B.C. and A.D. 500, excepting the seal which belongs to the Manteño culture (A.D. 500 to A.D. 1500).

In Classic Mesoamerica we again find this element very frequently among the Maya. It appears as façades in the shape of jaws at Copán (fig. 10), at Tikal (lateral entrante to the Group of the Columns), at Dxibilnocac, Tabasqueño, Río Bec, Uxmal, Hochob, and many other places.

These façades are most interesting inasmuch as they represent in a remarkable way those ideas that link the temple-doorway and the monstermouth, but we shall not repeat the analysis that Paul Gendrop has already carried out (1977).

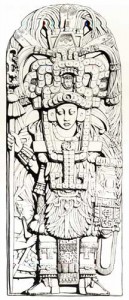

To continue, the Maya evidente the association of jaws-entrance together with the cult of caves, so diffused throughout the Post Classic Yucatán. We also see the link between headdresses-masks-jaws and the terrestrial monster in reliefs and stelae (fig. 11). In a way we can already join the snaketerrestrial monster-jaguar series to the façade-mask-headdress. The sequence could be first the monster-temple, then the façade-face (mask), with the mouth-doorway in the third place, all of them expressing one and the same thing.

Fig.10 Earth monster with two heads. The one on the right holds the corn god in its mouth. After Spinden 1957: pl. 52.

Fig.11 Stela A, Piedras Negras. The headdress worn by this personage represents the open jaws of a jaguar from which a small human head emerges. After Spinden 1957: fig. L.

Among the Maya, the representation of people coming out of the mouth of a snake or other similar animal is also quite common (fig. 12). The utilization of masks in decoration was highly important, and we have evidentes of this in the profusion of Chaac faces and faces of other gods that cover completely the Maya architecture (Foncerrada de Molina 1960). This obsession is not merely formal but rather the expression of a deeply rooted ideology. This is quite obvious in the depiction of stone huts on an inscription at Uxmal (Quadrangle of the Nuns), in the upper part of which a number of masks are observed that show the link between architecture and faces.

Surprisingly, in the region of Río Bec and the surrounding areas, an element is found that clearly shows the symbolic significante of façades: false doors and even false pyramids, When we look at them we realize that they were meant never to go into but to be seen from the outside, It seems that the main thing is their symbolic character, not their interiors,

We find similar cases all through Mesoamerican architecture, from the huge Teotihuacán basements which supported only small perishable temples on the tops to the stylized pyramids at Tikal, whose temples have very narrow chambers. The point was not the usefulness of the object itself but the image is offered.

In Teotihuacán, the importante of rituals in relation to caverns is also remarkable. Unfortunately we do not have texts of those times; but nevertheless we even now find caves Glose to ruins, Not only this, but the large cave under the Pyramid of the Sun has the shape of the Chicomostoc, the place of the mythical origin of the Nahua nations.

Later we again find this phenomenon in the Valley of Mexico and its surroundings, In Malinalco we have a magnificent temple, the entrante of which has the shape of a snake’s mouth, with all traits clearly marked: eyes, teeth, tongue, and mouth. The representation or a similar appears in the Codex Borgia (fig. 13), and according to the conquerors there was a circular temple dedicated to the worship of Quetzalcoatl among the Mexica of Tenochtitlán much resembling that of Malinalco (Marquina 1960).

Fig.12 Divine Maya serpent from whose open jaws a human personage with outstretched hand emerges. After Spinden 1957: fig. 93.

Fig.13 The doorway of this circular temple is represented by the open mouth of a serpent. The teeth and eyes can be seen. Codex Borgia.

Fig.14 Facade of Temple 1, Malinalco. This unique late building represents the mouth of the earth monster. The interior is circular. After Mendoza 1977:73.

In the specific case of Malinalco’s symbolism and the interpretation thereof, we already have Mendoza’s work (1977), In his publication the author proposes that the cave —since that is what the circular temple represents— is a large communicating door associated with the transit of the sun in terms of its extinction, in the moment of being swallowed by the earth monster (fig. 14), In the same way, the sun comes to life from the mouth of the jaguar —the cave— which is connected among the Matlanzincas to the cult of caverns.

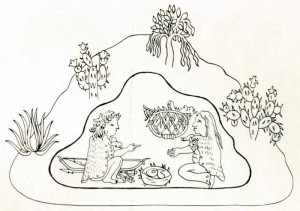

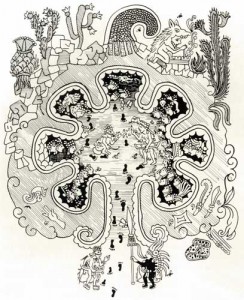

In some late manuscripts of the valley, there are dozens of figures in which the jaws-cave plays an important part, After the Aztec traditions of a mythical origin in the Chicomostoc or Seven Caves (fig. 15), we have many representations in which these jaws-caves appear, as well as mythical personages inside large caverns, Often the cave itself resembles a big throat, and even the chroniclers wrote indiscriminately of caves and mouths. We have it in Durán when he writes the history of Moctezuma Ilhuicamina, who sends his priests to rediscover the lost Chicomostoc, He says that it was «a big hill in the middle of water (where) there were some mouths or caverns or cavities» (fig. 16) (Durán 1967, 2: 216).

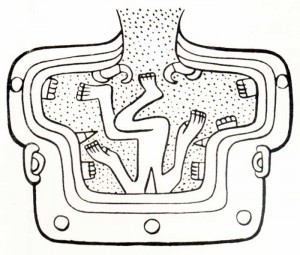

The concept of «coming out from the inside» was widespread throughout Post Classic Mesoamerica: the eagle-knights, the personages inside a turtle like Macuilxochitl (fig. 17); Quetzalcoatl, whose representation is a face within a feathered serpent as at Chichén Itzá; the coyote-knights, as those from Tula; the lizards with face-headdresses of Veracruz; the Maya jaguar-priest; and many others.

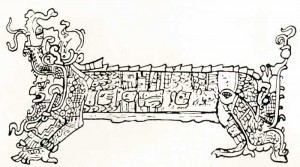

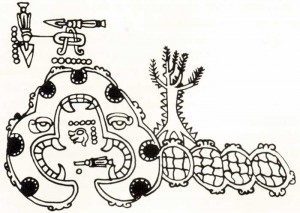

According to Joralemon, among the Maya the jaguar is the god of the underworld and the night, associated with God I, and it appears in art linked not only to funerals but also to the power of rulers, This god, which is also anthropomorphically represented, is in close contact with the bicephalous dragon of the Dresden Codex, a union between crocodiles and Itzamná (fig. 18), The Maya idea that the sun was day by day carried by a crocodile is also common among the Mexica with Xiucoatl.

Fig.16 Chicomostoc represented with a large animal from whose mouth emerges a group of Aztecans, the best ilustration of the earth monster association with a cave. Codex Durán. Drawings by A. Piña.

Fig.17 Stone figure representing the god Macuilxochitl, or 5 Flower, inside the mouth of a turtle. From Mixtequilla, Veracruz. National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico.

Fig.18 Two headed monster, possibly the earth monster, from whose open jaws emerges God D. Dresden Codex. After Spinden 1957: pl.90.

If we continue with the Maya and their religious contacts with the late inhabitants of the valley, we will find that both share an identical vision of the underworld, Let us point out that the Aztec Mictlán is quite similar to the Maya Xibalba, They both have many internal stages in which the gods of death dwell: Mictlantecuhtli, Hun Carné, and Vucub Carné. Even the Popol Vuh narrates Hun Hunahpu’s and Vucub Hunahpu’s descent into the underworld, and the altiplano manuscripts refer to Quetzalcoatl and his twin brother Xolotl.

One must remember that Xibalba was also a cave. In Occidental Mexico it appears that certain elements that we find among the Maya and the Mexica were repeated, in relation to death and to the representations of the underworld, as Furst has pointed out.

Now, after these preliminaries, we arrive at what we can consider basic conclusions, We can start with ethnography, which shows us the existente, in almost every surviving pre-Hispanic group, of rites associated with caves, The research work that best presents the problem of rituals connected to caverns is that of Heyden (1973, 1976), She proposes that these rites are ceremonies of some sort of change which legalize or legitimatize situations of transitions to different stages, usually of a cyclical or collective character.

The rituales are all closely related to each other, particularly because they usually deal with situations of incorporation or disincorporation in a group that might be social as well as mythological, Eventually, both ideas come together, as in the case of death, wherein one world is abandoned and the process recommences in another one.

Based on Heyden’s work (1976), the rites could be listed as follows:

- Rites of birth. Of gods (of a cosmogonic nature), of people, or of groups (of a social nature).

- Rites of initiation. Always related to social incorporation, baptims, or the entrace to adolescence or adulthood.

- Rites of illness and cure, of a social reincorporative nature, also implying a change or transit from one category to another.

- Rites of exorcism, Always of reincorporation into the social group.

- Sociopolitical ceremonies, These are situations that need to be «legalizad»; they are performed in association with caves, as in the case of investitures, ascensions to the throne, etc.

- Rites of death. These are of social disincorporation, of tombs, burials, sacrifices, or oblations.

Both in sixteenth-century writings and in modern ethnological researches, we find hundreds of cases that fit into these categories, To mention only one, Herrera has said that both the sun and the moon were born in a cave.

As to births (fig. 19), we have the particular case of the Nahua groups who consider the Chicomostoc or Seven Caves as the place of their mythical origin (figs. 20 – 22), This is mentioned in dozens of manuscripts, A most interesting fact is that these caves are also identified with the mouths of terrestrial monsters, Perhaps the best example of this occurs in the codex of Father Durán, Other examples are in the Selden Codex, the Ramírez Codex, the Tlotzín map, the Antonio de León Codex, the Mixtec manuscript of Ontario, the Toltec-Chichimecan history, the Jucutácato canvas, the Cave Codex, the Cuahutinchan map, the Huamantla Codex, and many others.

Fig.19 Traditional association of birth and a cave in the pre-Hispanic codices. Quinatzin map. Drawing by A. Piña.

Fig.20 The Chicomostoc of the Toltec-Chichimeca history of the Seven Caves. Culhuacán is represented in the upper portion. Drawing by A. Piña.

Fig.21 Another version of the Seven Caves, no longer a single cave but here seven separate caves. Codex Durán. Drawing by A. Piña.

Perhaps there were rites of initiation into secret societies, or rites of warriors, that were held in caves or in buildings representing caves, as in Malinalco, as is believed by García Payón (1946), Heyden (1976), and Mendoza (1977).

Also, the fact of being born in the Chicomostoc was a symbol of status and social hierarchy; in some manuscripts there are shown groups of rulers seated in front of a cave, showing their lineage of Aztlán, as, for example, in the Codex Xólotl.

And last we have death, whose implications and relationship with the underworld are evident in almost all human cultures, The underworld as a place destined to final rest is linked with tombs, with different types of burial, and with the corresponding ceremonies, Quetzalcoatl descended into hell in the interior of the earth, Xólotl is represented at the moment of being swallowed by a skeleton (death) or by the jaws of a serpent or huge monster (fig. 23).

According to Sejourné (1971: 253), «the snake representa substance, Her association with the feminine divinities of earth is represented by the open jaws of the reptile, In this case, the substance is equivalent to death, to nothing.»

And this might be associated, though we do not quite understand how, with Xipe and the rites of being born once more, of dressing in the skin of the dead who, in their belief, did not really die but in some way helped the rebirth of the entire social group.

We believe that, among the Chavín and the Olmec, a whole body of mythical and religious concepts was determined, This could be due to the fact that at that time, among those who created the great Formative cultures, a particular mode of production was definitely structured, which is expressed suprastructurally with the institutionalization of certain religious «patterns» and of a defined type of state and social relations.

In connection with this, Brüggemann (1977: 8) says that «the State becomes recognizable to people through the religious and political bureaucracy which organizes the substantial and spiritual necessities of the population, with a territory demographically structured in small agricultural groups recognizing a political, religious and administrative center,» Since that time and from these Formative centers, a coherent ideology, a pattern of social organization, a specific class structure, and a specific ritual begin rapidly to expand. We find the prototypical elements of that «official religion» throughout vast geographical distantes.

Fig.22 The Chicomostoc earth monster. Codex of the Mixtec manuscript. Royal Museum of Ontario. After Spinden 1957: pl. LXIVb.

Fig.23 A personage is being swallowed into the jaws of the earth, the entrance to the underworld. Codex Laud. After Sejourné 1971: fig. 89.

Possibly, by the end of the Formative Period, the religion already «institutionalized» by a dominant state had need to transform many different religious ideas into a cult with its own liturgy and specific imagery, which at the beginning was represented in stone and later in architecture, together with many other less lasting materials.

All this could be erroneously interpreted as the dispersion of certain ideas by «invaders» or «missionaries» or the like, but that would be as if we understood the Spanish conquest of America in terms of the diffusion of Catholic ideas only, without considering the entire association of sociopolitical and, most of all, economic situations which motivated it.

This hypothesis of the significance of early Olmec «official art» can later be applied also to the Tenochca, Although the ethnographical analogies are not absolutely valid by themselves, we are able to think that like many other habits (invariants?) these were gathered all through the cultural Mesoamerican development with no interruptions, from the construction of their pyramids and temples to the gods and associated rituals, In this connection, Aguilera’s 1977 work on the significance of official Tenochca art can be of great help.

She proposes that this kind of art together with religion are «the fundamental means of ideological penetration and of socio-political power.» She defines art in terms of its role within society, that is, in terms of practicality rather than aesthetics, «Official Tenochca art performed a role which was neither esthetic nor individual, but social, inasmuch as official artistic expressions are created for the entire community and not for one person; therefore, the social non-esthetic functions will explain what they mean».

She also says, «So, the most important social function of official Aztec art consisted in performing as an instrument of religion, because at the point of representing the basic forms of ideology, it molded the expression of the metaphysical experience, of destiny and of the values of individuals and society, and of the order and unity of the universe».

Another consideration, in connection with the aboye, is that of the role played by Culhuacán in the real and mythical history of the nations of the valley. As the chroniclers say, this place is closely associated both with the Chicomostoc and with Aztlán, We will remember that, in the Boturini Codex, Huitzilopochtli appears inside Culhuacán, in a cavern. According to this manuscript, the Aztec arrived near the place by boat, Sejourné (1970) has analyzed the problem, and she arrives at the conclusion that the three of them are one and the same thing.

We do not agree with that but, rather, believe that it all implies something more complicated; it could be a place in which different events occur (and perhaps one especially important event), such as regroupments of people, or perhaps the place from which they received a first ruler, Therefore, the link with the cave could be understood as a «site of investitures,» as we have mentioned before; the Chicomostoc might represent the sense of birth, of regroupment, of rebeginning, of being legitimated, of initiating an entrance into the great Valley of Mexico.

If we summarize again, we shall realize that certain features, invariant expressions of pre-Hispanic cosmogonic development, tend to unify, Obviously it is not our purpose to look for elements in common, inasmuch as that would be outside the scope of this paper, We want to demonstrate that the jaguar, the snake, and the monster of the earth, though clearly different one from the other, eventually tend to perform similar roles; and this is precisely what also happens with the façades-masks-faces and with the mouths-doorways.

The final result is seen in the concept of getting in and the opposite one of coming out. We have birth and death, illness and cure, light and darkness, interior and exterior, together with all the rituals associated with general social incorporation and disincorporation, We have Quetzalcoatl and Xólotl, the gods coming out of or getting into the throats of the earth: the birth of humankind. Perhaps all this that is so evident in many American cultures is nothing but the expression of one iden tical concept too elementary to be clearly shown: the idea of a prime god, of a mother-goddess, though in the true sense of «mother»; and perhaps some of these forms are only their representations.

A good example of this, if we take into consideration the many differences, is found in the Catholic religion, wherein the substantial representations show the images of Jesus and not of God, Also, anyone who knows, even superficially, colonial American architecture —not to mention European examples— knows the way in which the Holy Spirit was represented, As it was impossible to represent «a holy spirit,» it always appeared in the shape of a white dove. Imagine, then, the conclusions of an archaeologist of the future who did not know the Bible or the other texts which today clarify this phenomenon.

Perhaps the cultures and peoples we have been discussing, by imagining their origins in a nonexistent Chicomostoc-mouth, by creating associated rituals, by building temples whose façades are but the faces of the gods themselves, are day by day showing us this idea, It is essential that this matter should be handled at a purely conceptual level, with no formal implications.